[Review] You Don't Know JS: this & Object Prototypes

| Book | You Don’t Know JS: this & Object Prototypes |

| Author | Kyle Simpson |

| Link | https://github.com/getify/You-Dont-Know-JS/blob/master/this & object prototypes/README.md |

- Objects in JS

- Prototypes

- “Class”

- Behavior Delegation

Objects in JS

Source: You Don’t Know JS: this & Object Prototypes - Chapter 3: Objects

1. Type

Primary types (language types)

- number

- boolean

- string

- null

- undefined

- object

Many people mistakenly claim “everything in JavaScript is an object”, but this is incorrect. Objects are one of the 6 (or 7, depending on your perspective) primitive types. Objects have sub-types, includingfunction, and also can be behavior-specialized, like[object Array]as the internal label representing the array object sub-type.

What are object sub-types?

In JS, object sub-types are actually just built-in functions. Each of these built-in functions can be used as a constructor (that is, a function call with the new operator), with the result being a newly constructed object of the sub-type.

Why do we need object sub-types?

The primitive value "I am a string"is not an object, it’s a primitive literal and immutable value. To perform operations on it, such as checking its length, accessing its individual character contents, etc, aStringobject is required.the language automatically coerces a"string"primitive to aStringobject when necessary, which means you almost never need to explicitly create the Object form.

What is exactly the function?

Functions are callable objects which are special in that they have an optional name property and a code property (which is the body of the function that actually does stuff).

How to remember?

Excluding from the self-defined object, we can always use typeof first to check out the primary types and then use instanceof to find out its object sub-types.

2. Contents

Objects are collections of key/value pairs. The values can be accessed as properties, via.propNameor["propName"]syntax. Whenever a property is accessed, the engine actually invokes the internal default[[Get]]operation (and[[Put]]for setting values), which not only looks for the property directly on the object, but which will traverse the[[Prototype]]chain (see Chapter 5) if not found.

Properties have certain characteristics that can be controlled through property descriptors, such aswritableandconfigurable. In addition, objects can have their mutability (and that of their properties) controlled to various levels of immutability usingObject.preventExtensions(..),Object.seal(..), andObject.freeze(..).

Properties don’t have to contain values – they can be “accessor properties” as well, with getters/setters. They can also be either enumerable or not, which controls if they show up infor..inloop iterations, for instance.

Properties

In objects, property names are **always **strings. If you use any other value besides a string(primitive) as the property, it will first be converted to a string.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | |

Computed Property Names

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | |

Arrays

Arrays are objects. Be careful: If you try to add a property to an array, but the property name looks like a number, it will end up instead as a numeric index (thus modifying the array contents):

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

Duplicating Objects

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 | |

It’s hard to tell which of shallow and deep copy is right without the use case.

One subset solution is that objects which are JSON-safe (that is, can be serialized to a JSON string and then re-parsed to an object with the same structure and values) can easily be duplicated with:

1

| |

A shallow copy is fairly understandable and has far less issues, so ES6 has now defined Object.assign(..) for this task. Object.assign(..) takes a target object as its first parameter, and one or more source objects as its subsequent parameters. It iterates over all the enumerable (see below), owned keys (immediately present) on the source object(s) and copies them (via = assignment only) to target.

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

Property Descriptors

Prior to ES5, the JavaScript language gave no direct way for your code to inspect or draw any distinction between the characteristics of properties, such as whether the property was read-only or not. But as of ES5, all properties are described in terms of a property descriptor.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 | |

We can useObject.defineProperty(..)to add a new property, or modify an existing one (if it’sconfigurable!), with the desired characteristics.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | |

I consider this as something about plumbing facts, which features some higher level operations. Like

Seal: Object.seal(..) creates a “sealed” object, which means it takes an existing object and essentially calls Object.preventExtensions(..) on it, but also marks all its existing properties as configurable:false.

Freeze: Object.freeze(..) creates a frozen object, which means it takes an existing object and essentially calls Object.seal(..) on it, but it also marks all “data accessor” properties as writable:false, so that their values cannot be changed.

For details, check this section

[ [ Get ] ]

1 2 3 4 5 | |

ThemyObject.ais a property access, but it doesn’t just look in myObjectfor a property of the name a, as it might seem. According to the spec, the code above actually performs a[[Get]]operation (kinda like a function call:[[Get]]()) on themyObject. The default built-in[[Get]]operation for an object first inspects the object for a property of the requested name, and if it finds it, it will return the value accordingly.

One important result of this[[Get]]operation is that if it cannot through any means come up with a value for the requested property, it instead returns the valueundefined(instead of aReferenceError).

Define an **accessor descriptor **(getter and putter)

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 | |

Existence

We showed earlier that a property access likemyObject.amay result in anundefinedvalue if either the explicitundefinedis stored there or theaproperty doesn’t exist at all. So, if the value is the same in both cases, how else do we distinguish them?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | |

Theinoperator will check to see if the property is in the object, or if it exists at any higher level of the [[Prototype]] chain object traversal (see Chapter 5). By contrast, hasOwnProperty(..) checks to see if only myObjecthas the property or not, and will not consult the[[Prototype]]chain.

hasOwnProperty(..)is accessible for all normal objects via delegation toObject.prototype(see Chapter 5). But it’s possible to create an object that does not link toObject.prototype(viaObject.create(null)– see Chapter 5). In this case, a method call likemyObject.hasOwnProperty(..)would fail.

In that scenario, a more robust way of performing such a check isObject.prototype.hasOwnProperty.call(myObject,"a"), which borrows the basehasOwnProperty(..)method and uses_explicit_thisbinding(see Chapter 2) to apply it against ourmyObject.

3. Iteration

Thefor..inloop iterates over the list of enumerable properties on an object (including its[[Prototype]]chain). But what if you instead want to iterate over the values?

for..inloops applied to arrays can give somewhat unexpected results, in that the enumeration of an array will include not only all the numeric indices, but also any enumerable properties. It’s a good idea to usefor..inloops only on objects, and traditionalforloops with numeric index iteration for the values stored in arrays.

ES5 also added several iteration helpers for arrays, including forEach(..), every(..), and some(..).

forEach(..)will iterate over all values in the array, and ignores any callback return values.every(..)keeps going until the end or the callback returns afalse(or “falsy”) value, whereassome(..)keeps going until the end or the callback returns atrue(or “truthy”) value.

As contrasted with iterating over an array’s indices in a numerically ordered way (forloop or other iterators), the order of iteration over an object’s properties is **not guaranteed **and may vary between different JS engines. **Do not rely **on any observed ordering for anything that requires consistency among environments, as any observed agreement is unreliable.

You can also iterate over **the values **in data structures (arrays, objects, etc) using the ES6for..ofsyntax, which looks for either a built-in or custom@@iteratorobject consisting of anext()method to advance through the data values one at a time.

Prototypes

Source: You Don’t Know JS: this & Object Prototypes - Chapter 5: Prototypes

1. My understanding

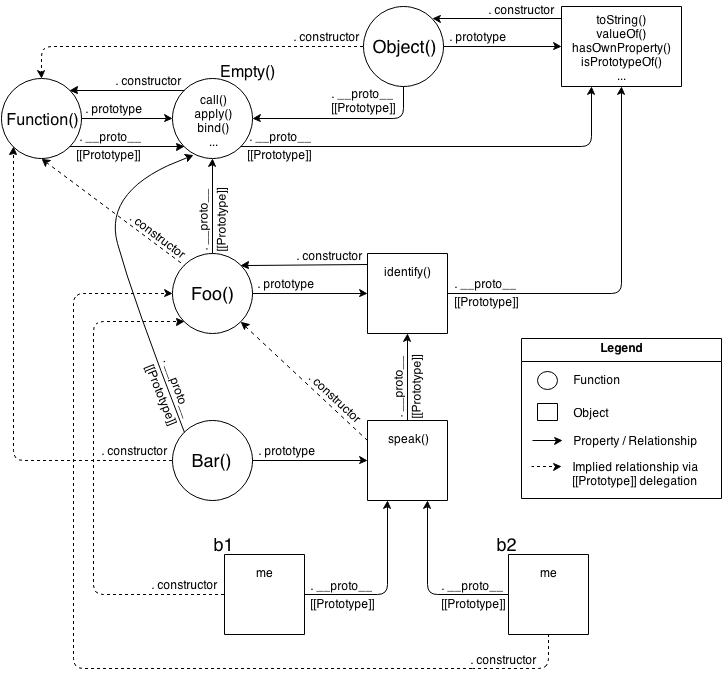

After reading this part, I realize that Arary, Function, Objectare all functions. I should admit that this refreshes my impression on JS. I know functions are first-class citizen in JS but it seems that it is all built on functions. Every object is created by functions:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 | |

2. What is a prototype?

Objects in JavaScript have an internal property, denoted in the specification as[[Prototype]], which is simply a reference to another object. Almost all objects are given a non-nullvalue for this property, at the time of their creation.

3. How to get an object’s prototype?

via __proto__or Object.getPrototypeOf

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 | |

So where is __proto__defined? Object.prototype.__proto__

We could roughly envision __proto__ implemented like this

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 | |

**Note: **The JavaScript community unofficially coined a term for the double-underscore, specifically the leading one in properties like__proto__: “dunder”. So, the “cool kids” in JavaScript would generally pronounce__proto__as “dunder proto”.

4. What is the prototype ?

prototype is an object automatically created as a special property of a function, which is used to establish the delegation (inheritance) chain, aka prototype chain.

When we create a function a, prototype is automatically created as a special property on a and saves the function code on as the constructor on prototype.

1 2 3 | |

I’d love to consider this property as the place to store the properties (including methods) of a function object. That’s also the reason why utility functions in JS are defined like Array.prototype.forEach() , Function.prototype.bind(), Object.prototype.toString().

Why to emphasize the property of a function?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

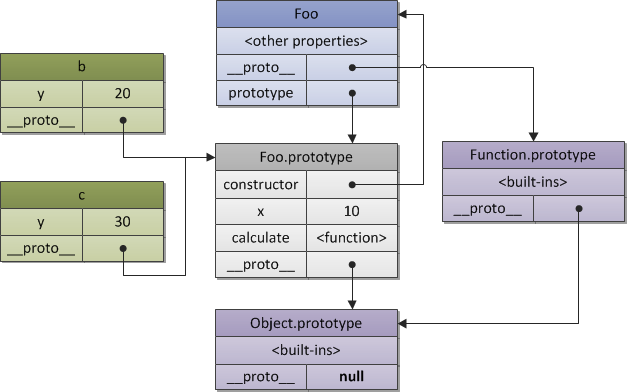

5. What’s the difference between __proto__ and prototype?

__proto__a reference works on every object to refer to its [[Prototype]]property.

prototype is an object automatically created as a special property of a function, which is used to store the properties (including methods) of a function object.

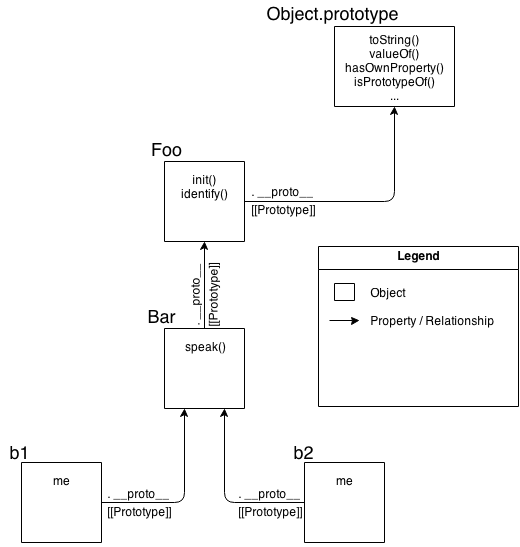

With these two, we could mentally map out the prototype chain. Like this picture illustrates:

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

Refer to: __proto__ VS. prototype in JavaScript

6. What’s process of method lookup via prototype chain?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 | |

The top-end of every _normal _[[Prototype]]chain is the built-in Object.prototype. This object includes a variety of common utilities used all over JS.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 | |

“Class”

Source: You Don’t Know JS: this & Object Prototypes - Chapter 4: Mixing (Up) “Class” Objects

1. Misconception

There’s a peculiar kind of behavior in JavaScript that has been shamelessly abused for years to hack something that looks like “classes”. JS developers have strived to simulate as much as they can of class-orientation.

JS has had some class-like syntactic elements (likenewandinstanceof) for quite awhile, and more recently in ES6, some additions, like theclasskeyword (see Appendix A). But does that mean JavaScript actually has classes? Plain and simple: No.

**Classes mean copies. **JavaScript **does not automatically **create copies (as classes imply) between objects.

Read You Don’t Know JS: this & Object Prototypes - Chapter 4: Mixing (Up) “Class” Objects for details:

- Why does JavaScript not feature class inheritance?

- Why does mixin pattern (both explicit and implicit) as the common sort of emulating class copy behavior, not work in JavaScript?

2. “Constructors”

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 | |

TheFoo.prototypeobject by default (at declaration time on line 1 of the snippet!) gets a public, non-enumerable property called.constructor, and this property is a reference back to the function (Fooin this case) that the object is associated with.

Does “constructor” mean “was constructed by”? NO!

The fact is,.constructoron an object arbitrarily points, by default, at a function who, reciprocally, has a reference back to the object – a reference which it calls.prototype. The words “constructor” and “prototype” only have a loose default meaning that might or might not hold true later. The best thing to do is remind yourself, “constructor does not mean constructed by”.

What is exactly a “constructor”?

In other words, in JavaScript, it’s most appropriate to say that a “constructor” is any function called with thenewkeyword in front of it. Functions aren’t constructors, but function calls are “constructor calls” if and only ifnewis used.

Do we have to capitalize the constructor function? NO!

By convention in the JavaScript world, “class”es are named with a capital letter, so the fact that it’s Foo instead of foo is a strong clue that we intend it to be a “class”. But the capital letter doesn’t mean anything at all to the JS engine.

1 2 3 4 5 | |

In reality,Foois no more a “constructor” than any other function in your program. Functions themselves are not constructors. However, when you put thenewkeyword in front of a normal function call, that makes that function call a “constructor call”. In fact,newsort of hijacks any normal function and calls it in a fashion that constructs an object, in addition to whatever else it was going to do.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 | |

NothingSpecialis just a plain old normal function, but when called withnew, it constructs an object, almost as a side-effect, which we happen to assign to a. The call was a constructor call, but NothingSpecial is not, in and of itself, a constructor.

Is .constructorreliable to be used as a reference? NO!

Some arbitrary object-property reference likea1.constructorcannot actually be trusted to be the assumed default function reference. Moreover, as we’ll see shortly, just by simple omission,a1.constructorcan even end up pointing somewhere quite surprising and insensible.a1.constructoris extremely unreliable, and an unsafe reference to rely upon in your code.Generally, such references should be avoided where possible.

.constructoris not a magic immutable property. It is non-enumerable (see snippet above), but its value is writable (can be changed), and moreover, you can add or overwrite (intentionally or accidentally) a property of the nameconstructoron any object in any[[Prototype]]chain, with any value you see fit.

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

If you create a new object, and replace a function’s default.prototypeobject reference, the new object will not by default magically get a.constructoron it.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

What’s happening?a1has no.constructorproperty, so it delegates up the[[Prototype]]chain toFoo.prototype. But that object doesn’t have a.constructoreither (like the defaultFoo.prototypeobject would have had!), so it keeps delegating, this time up toObject.prototype, the top of the delegation chain.That object indeed has a.constructoron it, which points to the built-inObject(..)function.

Of course, you can add.constructorback to theFoo.prototypeobject, but this takes manual work, especially if you want to match native behavior and have it be non-enumerable.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 | |

That’s a lot of manual work to fix.constructor. Moreover, all we’re really doing is perpetuating the misconception that “constructor” means “was constructed by”. That’s an expensive illusion.

3. What happened when we callnew ?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 | |

- It creates a new object. The type of this object, is simply object

- It sets this new object’s internal, inaccessible, [[prototype]](i.e. __proto__) property to be the constructor function’s external, accessible, prototype object (every function object automatically has a prototype property).

- It makes the

thisvariable point to the newly created object. - It executes the constructor function, using the newly created object whenever

thisis mentioned. - It returns the newly created object, unless the constructor function returns a non-

nullobject reference. In this case, that object reference is returned instead.

Reference

4. Introspection

instanceof

1

| |

Theinstanceofoperator takes a plain object as its left-hand operand and afunctionas its right-hand operand. The questioninstanceofanswers is:in the entire[[Prototype]]chain ofa, does the object arbitrarily pointed to byFoo.prototypeever appear?

What if you have two arbitrary objects, sayaandb, and want to find out if the objects are related to each other through a[[Prototype]]chain?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 | |

Object.prototype.isPrototypeOf()

1

| |

The questionisPrototypeOf(..)answers is:in the entire[[Prototype]]chain ofa, doesFoo.prototypeever appear?

What if you have two arbitrary objects, sayaandb, and want to find out if the objects are related to each other through a[[Prototype]]chain?

1 2 3 | |

Behavior Delegation

Source: You Don’t Know JS: this & Object Prototypes - Chapter 6: Behavior Delegation

1. My understanding

Considering we don’t actually have class in JavaScript, but we want the benefit of behaviour sharing around code entities. JavaScript employs behaviour delegation as the [[Prototype]]mechanism. It kinda differs from the traditional class-instance thinking, but it’s still in the spectrum of OO, as a form of plain objects linking (delegation) instead of inheritance.

Classical inheritance is a code arrangement technique. For the cost of arranging objects in a hierarchy, you get message delegation for free. Delegation arranges objects in a horizontal space (side-by-side as peers) instead of a vertical hierarchy. So, can I say one outweighs another between behaviour delegation and traditional class theory? No, they are different assumptions that we don’t have true class in JavaScript.

Behavior delegation looks like a side-effect outcome on the way JavaScript strives to simulate class-oriented code to meet the expectations of most OO developers. For instance, new creates an automatic message delegation just like inheritance, name of constructor , introducing classin ES6. It’s probable that people added prototype aiming to simulate class behaviours.

Anyway, behaviour delegation works and I consider it as the right mental model to illustrate the chaos in JavaScript, which is much better than the contrived class thinking.

2. Background

JavaScript is almost unique among languages as perhaps the only language with the right to use the label “object oriented”, because it’s one of a very short list of languages where an object can be created directly, without a class at all.

In JavaScript, there are no abstract patterns/blueprints for objects called “classes” as there are in class-oriented languages. JavaScript just has objects. In JavaScript, we don’t make copies from one object (“class”) to another (“instance”). We make links between objects.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | |

Whenais created by callingnew Foo(), one of the things (see Chapter 2 for all four steps) that happens is thatagets an internal[[Prototype]]link to the object thatFoo.prototypeis pointing at. We end up with two objects, linked to each other.

The actual mechanism, the essence of what’s important to the functionality we can leverage in JavaScript, is all about objects being linked to other objects.

Compared to traditional inheritance

In class-oriented languages, multiple copies (aka, “instances”) of a class can be made, like stamping something out from a mold. But in JavaScript, there are no such copy-actions performed. You don’t create multiple instances of a class. You can create multiple objects that [[Prototype]]link to a common object. But by default, no copying occurs, and thus these objects don’t end up totally separate and disconnected from each other, but rather, quite linked.

“inheritance” (and “prototypal inheritance”) and all the other OO terms just do not make sense when considering how JavaScript actually works (not just applied to our forced mental models).

Instead, “delegation” is a more appropriate term, because these relationships are not **copies but delegation links.

Prototypal Inheritance && Differential Inheritance

This mechanism is often called “prototypal inheritance” (we’ll explore the code in detail shortly), which is commonly said to be the dynamic-language version of “classical inheritance”. The word “inheritance” has a very strong meaning (see Chapter 4), with plenty of mental precedent. Merely adding “prototypal” in front to distinguish the actually nearly opposite behavior in JavaScript has left in its wake nearly two decades of miry confusion.”Inheritance” implies a copy operation, and JavaScript doesn’t copy object properties (natively, by default). Instead, JS creates a link between two objects, where one object can essentially delegate property/function access to another object. “Delegation” is a much more accurate term for JavaScript’s object-linking mechanism.

Another term which is sometimes thrown around in JavaScript is “differential inheritance”. The idea here is that we describe an object’s behavior in terms of what is different from a more general descriptor. For example, you explain that a car is a kind of vehicle, but one that has exactly 4 wheels, rather than re-describing all the specifics of what makes up a general vehicle (engine, etc).

But just like with “prototypal inheritance”, “differential inheritance” pretends that your mental model is more important than what is physically happening in the language. It overlooks the fact that object Bis not actually differentially constructed, but is instead built with specific characteristics defined, alongside “holes” where nothing is defined. It is in these “holes” (gaps in, or lack of, definition) that delegation can take over and, on the fly, “fill them in” with delegated behavior.

3. Create delegations by Object.create

Object.create(..) creates a “new” object out of thin air, and links that new object’s internal [[Prototype]]to the object you specify.

1 2 3 4 5 | |

How to make plain object delegations?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | |

How to make delegations to perform “prototypal inheritance”?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | |

Inspection: Bar.prototype has changed

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | |

Inspection: Bar.prototype is not a reference (separated) to Foo.prototype

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | |

Why not?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 | |

ES6-standardized techniques

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

How to envision your own Object.create?

This polyfill shows a very basic idea without handling the second parameter propertiesObject.

1 2 3 4 5 | |

Polyfill on Object.create - MDN

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 | |

4. Towards Delegation-Oriented Design

Pseudo-code for class theory

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 | |

Pseudo-code for delegation theory

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 | |

Avoid shadowing (naming things the same) if at all possible

With the class design pattern, we intentionally namedoutputTaskthe same on both parent (Task) and child (XYZ), so that we could take advantage of overriding (polymorphism). In behavior delegation, we do the opposite: we avoid if at all possible naming things the same at different levels of the[[Prototype]]chain (called shadowing), because having those name collisions creates awkward/brittle syntax to disambiguate references, and we want to avoid that if we can.

This design pattern calls for less of general method names which are prone to overriding and instead more of descriptive method names, specific to the type of behavior each object is doing.This can actually create easier to understand/maintain code, because the names of methods (not only at definition location but strewn throughout other code) are more obvious (self documenting).

Setting properties on an object was more nuanced than just adding a new property to the object or changing an existing property’s value. Usually, shadowing is more complicated and nuanced than it’s worth, so you should try to avoid it if possible.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 | |

Though it may appear thatmyObject.a++should (via delegation) look-up and just increment theanotherObject.aproperty itself in place, instead the++operation corresponds tomyObject.a = myObject.a + 1.

That’s the reason why we use delegation on prototype chain, we should avoid using the same name as traditional class inheritance would do.

Save state on delegators

In general, with[[Prototype]]delegation involved, you want state to be on the delegators(XYZ,ABC), not on the delegate (Task). We benefit it from the implicit call-site thisbinding rules.

Comparison

OO style

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 | |

OO style features constructor which introduces a lot of extra details that you don’t technically need to know at all times.

OLOO style

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 | |

OLOO-style code has vastly less stuff to worry about, because it embraces the fact **that the only thing we ever really cared about was the **objects linked to other objects.